Essays

The Trunks

by Reiko Fujii

As my mother, aunts, uncles, and I rummaged through the boxes and musty trunks in the barn and under the tractor shed, I was thrilled to discover relics from my mother’s family’s past. Still tied to one of the trunks was a worn-out tag that read “MISSOURI PACIFIC LINES — COMPANY MATERIAL — HURRY THROUGH.” Although faded, my grandfather’s name and address were clearly printed on the lines below. The trunks were filled with old baby clothes, worn and faded little girls’ dresses, boys’ mended coveralls, a woman’s threadbare dress, and old-fashioned one-piece bathing suits. I was witnessing the truth of the words I had heard throughout my life, “Grandma never threw anything away.”

Grandpa had passed away in December 1979. After Grandma died in May 1984, one of her twenty-three grandchildren decided to stay on the farm and raise his family there. Our beloved Inaba farm continued to stay in our family, extending this legacy to a total of four generations, eighty years.

Grandpa had built the barn and the chicken houses and worked in the fields until he was seventy. Grandma had collected eggs, weeded the fields, and cleaned the chicken coops from dawn until dusk every day since she came from Japan to marry Grandpa in 1924. Their seven children were brought up on the land. The oldest ones had been born in their small home, which was a remodeled chicken house. Grandpa had added on a bedroom, a closet, and a small bathroom. The family took their baths in a Japanese-style bathhouse called an % ofuro,% which was located outside the main house. Eventually, the old house was replaced with a new modern house, but everyone still took baths in the ofuro.

In 2002 the unimaginable happened. The farm was sold to a developer and would be completely demolished, making way for a new housing track. Almost everything had to be given away or sold.

“Where did these trunks come from?” I wondered out loud. Aunt Haru remembered, “The metal ones were ordered through the Sears Roebuck catalog. Grandpa made the wooden trunks.” Uncle Aki, looking over the rim of his glasses, was reminded, “My dad was not only the camp barber, he was also a talented carpenter and handyman. He was called the ‘Fix-it’ man in camp because he had a shop set up in a small trailer.”

I crouched over the old trunks, keepers of forgotten memories from sixty years ago. As I examined every piece of tattered clothing, my seventy-five-year-old mother and her younger sister, Haru, recalled their experiences as prisoners in the Manzanar concentration camp and Crystal City “family” camp. I discovered a wadded-up brown, red, and multicolored hand-knitted sweater-vest buried beneath the old children’s clothes. This should be thrown out I thought. My mother held it up and then turned it right side out. “Mom made this in camp,” she recalled. “She kept adding to it, using up leftover yarn. She even wore it after she returned to the farm because it kept her warm in the wintertime.” With loose ends of yarn poking out here and there, I could see that my grandmother meticulously mended her frayed vest over and over again. % We had better keep this vest after all. It was a part of not only Grandma’s life but also American history,% I reflected.

Aunt Haru, a spry seventy-three-year-old, commented on a pair of worn-out young boy’s coveralls with tattered straps attached by safety pins, “Oh, I remember, Tony used to wear these kinds of coveralls when he was little. He sure got good use out of these!” Uncle Tony was born one month before Grandma and her seven children were forced to leave their farm to live in the desert at the Manzanar prison camp. Grandpa and his brother, Hideo, had been arrested on the streets of downtown Riverside as highly suspicious “enemy aliens” weeks before Uncle Tony was born.

How did my non-English-speaking, eight-months pregnant grandmother feel when the FBI agents, for no understandable reason, took her husband away in their black car? How did she and her children prepare to leave their chickens and farm for an unknown amount of time? How were they going to be able to keep their property? Aunt Haru had heard her father explain, “After the war broke out, we still owed half the payment on the farm. We had about five thousand chickens when we were forced to leave. We sold all of the chickens. We sold almost everything and paid off the rest of the land. This was how we were able to keep the farm.”

Almost a year and a half passed before the government allowed Grandpa to be reunited with Grandma and their seven children at the Crystal City “family” prison camp in Texas. Grandpa met his youngest son, Tony, for the first time when he was a toddler.

As they rummaged deeper into the trunks, Aunt Haru and Mom found old-fashioned bathing suits at the bottom of one. “Crystal City had a swimming pool that everyone helped to build. We all went swimming there. It was the only way to cool down from the intense summer heat. One day, two of the Japanese Peruvian girls drowned,” Aunt Haru sadly remembered. “Japanese from South America were imprisoned there because they were kidnapped by the U.S. government to be used in hostage exchanges with the Japanese government.”

I later found out that 2,264 men, women, and children from twelve Latin American countries were forcibly deported to the United States during the war. When the war ended, they were not allowed back into their former countries, and the United States did not want them to stay here because they were considered illegal aliens. As a result, most of the Japanese from South America lost everything, including their country. [note no.1]

The knitted garment, the coveralls, the bathing suits—all these old clothes worn by my mother, aunts, and uncles in the prison camps—were pungent reminders of a dark slice of American history. I could now look at and touch the loose threads and fabrics, a tapestry symbolizing the experiences of 120,000 Nisei and Issei in the deserts where they were forced to live. Although my grandparents’ family was one of the few who did not lose their property during the war, they suffered racial prejudice, monetary loss, and theft of their personal belongings.

As the trunks were closed, sealing my family’s past in darkness, it became clearer to me that the ramifications from my family’s unjust imprisonment, especially the psychological trauma, were continuing to haunt not only them, but also my generation.

Reiko Fujii

1. Roger Daniels, Sandra C. Taylor, and Harry H. L. Kitano, eds., Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress, rev. ed. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991).

Journal from Japan Trip

November 4–10, 2002

by Reiko Fujii

At 9:00 a.m. Aunt Fumiko, Mom, Dad, Bob, and other family members, along with our good friends Pat Mayo and Sambodh, left Nara to take a two and a half hour train ride to Susami. While eating a delicious obento (Japanese lunch) on the train, I looked out at the passing rice paddies. Raindrops started to splatter on the windows as we whizzed by. I had heard we might be encountering a wet weekend.

After warm greetings from my cousins, who met us at the tiny Susami train station, we climbed into three cars, two of which went directly up the mountain to a cemetery in Samoto. My father’s mother grew up in this mountain farming village about a hundred years ago.

In pouring rain, we climbed the slippery, uneven stone steps up the side of the mountain to the top of the cemetery, where my father’s mother’s ancestors were buried. We offered flowers and paid our respects, then walked down the treacherous steps back to the cars. I wanted to wear the kimono in the cemetery, but the rain, the weight of the kimono, and the number of slippery stairs seemed a barrier. Everyone encouraged me to wear it in spite of these imagined obstacles.

The weather collaborated with us, stopping the rain for twenty minutes. (As a myriad of mosquitoes appeared, I wondered if any of them were descendants from the time my ancestors lived there a hundred years ago.) We had enough time to document the presence of the kimono and three living generations: my father, my second-cousin, and me. On our way back to the cars, the torrential rain suddenly began again.

Aunt Fumiko, who had gone directly to the hotel from the train station, was excited to hear about our experience in the Samoto cemetery. She felt it was a good omen from our ancestors that the rain stopped for the twenty minutes I was wearing my Glass Ancestral Kimono.

Bob, Pat, Sambodh, and I decided to sleep in the house my father and his family built sixty-three years ago. Since there was talk about the house being haunted, I was wondering if the ghosts would appear. I mistakenly thought I heard them when Sambodh started snoring.

We woke up at 5:00 a.m. We wanted to videotape my wearing the kimono on the pier at dawn. There was not much of a sunrise because of all the clouds, but the reflection of the light on the waves was stunning. The ocean breeze was refreshing as I walked on the concrete breakwater, feeling the weight of the glass kimono and recalling my ancestors.

Later that morning, we strolled around the small fishing village of Esumi, searching for the old moss-covered wall where I dreamt of having an ancestral walk. We found the tiny street tucked away near the railroad tracks.

The ancestral walk took place at about 9:15 a.m. The street was so small and secluded that there were no townspeople around to walk with us. The solemn feeling of reverence was almost missing because everyone was having such a great time laughing and lining up along the wall, waiting to join the procession. I still felt I was living in a dream as my family was honoring and being honored in this unusual way.

The thirteenth anniversary memorial service of my Uncle Akio’s death was held after the ancestral procession. The Buddhist priest’s chanting was soothing. I loved the feeling of wholeness from being present with all of these important people in my life. I can still hear my relatives rhythmically chanting in unison, with the drum-like sound coming from the priest’s hitting the huge carved-wood gourd.

For the remainder of the service, we all walked over to the cemetery, where my father’s brother, Akio, and our ancestors were buried. I was surprised and honored that the Obo-san (priest) asked me to wear the kimono at the gravesite. I was so deeply touched that tears kept streaming down my face while I wore the kimono. I stood next to the 400-year-old headstones and bowed to all of my ancestors. During this most profound moment, I felt an honored connection and overwhelming appreciation for those ancestors and for my father, my mother, Aunt Fumiko, my family, all of my other relatives, my friends, and the rest of humanity. I felt a deep connection to myself.

There was hardly time to wipe away my tears, for directly after the ceremony Pat and I had to hurry down the street to the only beauty parlor in Esumi. My hair was expertly put up and red lipstick and face powder applied. Aunt Fumiko, her cousin, Mrs. Ogura, and I were finally going to do the performance with the Glass Ancestral Kimono at the luncheon honoring Uncle Akio.

When we arrived at the reception, the kimono was quickly placed on my shoulders and arms, and I immediately went to the room where everyone was waiting. As I walked in, the glass gently struck together, sounding like wind chimes.

I held back my tears when Aunt Fumiko started to sing her favorite Japanese song, which reminded her of her late husband, Akio. It was touching to hear her lovely voice accompanied by the singing of her cousin and Mrs. Ogura playing the koto-like instrument.

After the performance and having eaten from the delicious array of assorted sushi, I sat down near the Obo-san to let him know how much I appreciated being invited to wear the glass kimono in the cemetery. Through the words of my father, who was the translator, the Obo-san told me how special it was for the ancestors to be honored in this way. He felt that young people were turning away from the tradition of honoring their ancestors. This was perhaps a contemporary way for them to remember their ancestors.

The Obo-san mentioned that he remembered meeting me six years earlier, when I made my first trip to Esumi: I was standing outside the Buddhist Temple with Aunt Fumiko and my cousin Kazumi. The Obo-san, wearing a hat to shade his head from the June sun, was working on the grounds with his wife and two children. He came over to greet us. Aunt Fumiko explained that I was from America, coming to visit the land of my ancestors. He walked over to a bush and started talking about its one and only flower. It was translated to me that he had planted this bush ten years earlier, when he first came to the Esumi temple from Kyoto. This was the first time it bloomed. The simple azalea-like flower would last only for one day. The Obo-san claimed that it was auspicious for me to be there to witness that flower.

Reiko Fujii

Lordsburg Internment Camp, New Mexico

by Reiko Fujii

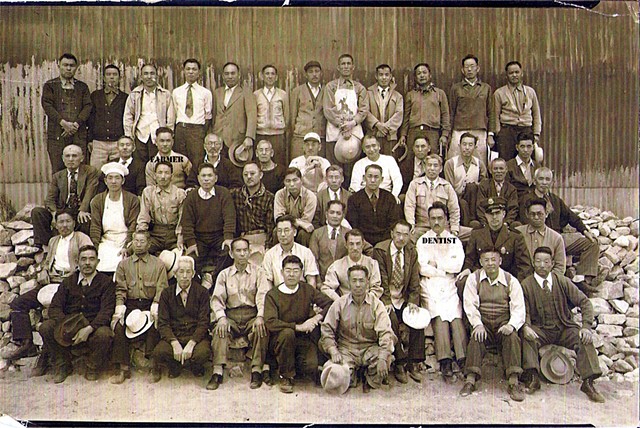

During WWII, my maternal grandfather, Chikayasu Inaba, was imprisoned in several internment camps in the United States. One of these locations, Lordsburg, held the U.S. Army’s largest number of Issei (first-generation Japanese immigrant) prisoners, with a population peaking at 1500. Four months after my grandfather and his brother arrived at Lordsburg, a disturbing incident occurred that, even within the larger tragedy of the internment of Japanese Americans, stands out for its sheer brutality.

On July 27, 1942, Toshio Kobata and Hirota Isomura, two elderly Issei, were shot and killed by a guard who claimed they were running away to escape. After a military investigation, the guard, Private First Class Clarence Burleson, was found not guilty. The official explanation asserted that he had lawfully killed them, even after many of the prisoners testified that Kobata and Isomura were both physically unable to run.

According to his friend Hiroshi Aisawa, Kobata had suffered from tuberculosis for sixteen years, causing him to become disabled. Fukujiro Hoshiya, a good friend of Isomura, testified that Isomura had an injured spine: “At the Bismarck Camp, he walked with a very much stoop. He hurt his spine about ten years ago falling off a boat.” [note no.1]

A fellow prisoner, Sematsu Ishizaki, claimed that the deaths of Kobata and Isomura were ordered by Colonel Clyde Lundy, the prison camp’s commandant. Isomura and Kobata had been involved in a protest challenging the illegal working conditions at the camps. The prisoners knew the forced labor they were subjected to was illegal under the Geneva Convention and they pressed for fair treatment under that standard. Their suit eventually led the Eighth Army headquarters at Fort Bliss to retire Lundy, close the camp at Lordsburg, and move almost everyone to Camp Santa Fe. [note no.2]

My grandfather was transferred to Crystal City Family Camp in Texas, where he was reunited with his family after months of separation. There he finally met his youngest son, one-year-old Tony, for the first time.

Reiko Fujii

1. Transcript of Court Martial 9-10-42, Lordsburg Internment Camp, Lordsburg, New Mexico. From records of Ted Kashima, PhD, University of Washington, Seattle, WA Pages 55-56

2. Many Mountains Surrounding:http://www.manymountains.org/lordsburg