Press

Articles and Interviews

"Reiko Fujii, The Glass Kimono," Works and Conversations Magazine

The Glass Kimono: Some Reflections on the films of Reiko Fujii - Richard Whittaker

"'I had a dream,' the narrator says, 'of making a glass, ancestral kimono.' Reiko's film is less than five minutes long, but right away we're delivered from the ordinary into the realm of dreams and magic: a glass, ancestral kimono. The mysteriousness of the phrase is subliminal..."

"Message from the President," Glanc Newsletter, Autumn 2009

Glass Quarterly Magazine

Book Works 2006, Stephen P. Corey Award, page 29

Art as Healing and Transformative

by Judy Shintani

Reiko Fujii’s work brings grown men to tears. Entering into the presence of her art should not be done lightly. Each piece is exquisite, a jewel created with intention. Not limited by a particular medium, Reiko chooses the materials and method that can best communicate the depth, texture, and feeling she wants to convey. The variety of materials (glass, paper, fabric, paint, performance, or video) and the expertise of craftsmanship make her work even more intriguing.

To say that Reiko’s work is transformative would be an understatement. The art-making process fuels her creativity. She dives into her emotional state, working with sadness, anger, and joy to create masks, boxes with mirrors, books, paintings, and glass garments. Art-making and the community of artists have drawn Reiko out: once a very private person, she now exhibits and talks about her work, explaining her use of art as a process for understanding and exploration.

Her empathetic investigation of how immigration, isolation, culture, gender issues, and imprisonment affected her ancestors and influence future generations is not unlike the study an anthropologist would conduct. Using artifacts including family clothing, photographs, and barn wood, she takes ordinary objects and infuses them with history and narrative so that others can relate the stories to their own lives. It is as if these stories must be told, must have the light shone on them, and must be released for transformation to occur.

Reiko’s pieces remind me of shrines, honoring self-exploration, family, ancestors, and unsung heroes she has crossed paths with. When Reiko slips into the translucent shrine of one of her glass kimonos, her ancestors are walking with her, the tinkling crystal sound calling them forth. When she inscribed her grandmother’s life story onto a mended piece of kimono and placed the cloth book in an old sugar canister that once held the family farm’s produce sales money, she repurposed a dormant piece of history into a treasure trove for memories. Many of Reiko’s works beckon the viewer to come closer, to inspect the detail and get lost in their intricate stories. Hours of pondering await anyone thumbing through the many library catalog cards she painted, drew, collaged, and sewed with her own hair—particularly wonderful moments and memories that fill the drawers of her Curating Joy installation.

Reiko’s transformation of the ordinary into the extraordinary reminds us that beauty is everywhere. The meditative manner in which she creates allows her understanding and devotion to unfold at a quiet and measured pace as she embodies the work over weeks, months, and years. The completed art, glowing with meaning and love, continues to transform not only herself, but also the world around her.

Judy Shintani, Asian American Women Artists Association

Journey of the Glass Kimono Introduction

by Bob Jecmen

An eerie sound of wind chimes mixes musically with the gentle rolling surf. Two fishermen pause from attending their gear and stare out at the ghostly figure walking slowly on the distant concrete pier. The early morning light colors the old men’s weathered faces as they watch the light sparkle off the hundreds of glass pieces adorning this mysterious figure. Reiko Fujii, wearing her Glass Ancestral Kimono, raises her arms to the sea as she walks to the end of the pier amidst the serenade of tinkling glass in the gentle morning breeze.

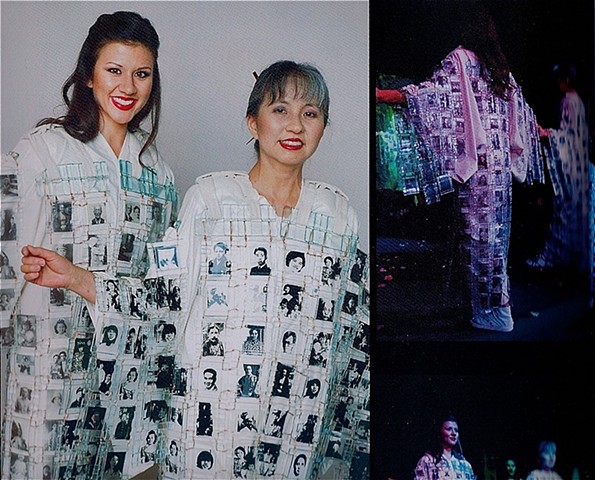

Reiko has created a wearable kimono out of thousands of pieces of glass fused into 224 squares, each with an image of one or more of her ancestors. The fused glass squares generate a rich texture to frame the images. The kimono is woven together by an intricate set of copper wire ties, allowing the individual glass pieces to move and strike each other, creating a haunting sound as she walks wearing her tribute to the many generations of her family who form her roots.

Reiko’s glass kimono began as a way to honor her ancestors. Since then, it has become much more. It is not only a connection of the past with the present but also a catalyst for bringing together her living family. It is art that transcends time and culture. It celebrates the human experience and leaves a lasting impact on all those who see and hear it.

Bob Jecmen

A Sparkle on the Ancestral Sea of Time

by George Havelka

Where were we before we were here? Can we sense previous manifestations? How shall we honor those that went before, acknowledge that we are a precursor to many yet to come, and still be in the now, all at the same time? Could the past intertwine with the present and future in ways that are hidden from us?

The work of Reiko Fujii dwells on and displays a personal exploration of these questions. In so doing, she asks us to take part in our own search for our place in the continuum.

In her opening Dance of Grief performance, while wearing successive masks and beckoning and rocking with an initial violence that then slows to a soft acceptance, Fujii, in ghostlike black, embodies a visually striking and emotional representation of a spirit beyond time, watching as each player takes a turn.

Fujii’s work takes cues from Japanese ancestral rites, yet is more inclusive. Observing the videos of relatives and assorted friends at the old family farm in Riverside, California, one’s mind easily moves to personal histories. The smiles, shared work, postures, and eating scenes remind all in the audience of some aunt or cousin, parent or friend.

Fujii, having been told that the family farm’s old barn was going to be torn down to make way for the usual bout of Southern California suburban progress, made her way there for one last look. The backdrop for her performance is a large section of wall she rescued from the barn. Old phone numbers and other farm data are written in chalk on the wall.

Fujii describes the contents of an antique trunk: letters and pictures, clothing and a clothesline saved from the internment camps. Her narrative describing the use and meaning of each item enriches our travel back and forth through time.

Installed to the side of the barn wall is the politically powerful and emotionally charged “Grandfather’s Letter.” Ancestor Inaba’s petition, dated 9-30-42, is enlarged for all to read. He is asking that his case be reopened so that he might be allowed to reunite with his wife and seven children, who had been taken to the Manzanar Relocation Center. Pledging loyalty to the United States, Inaba describes himself as “materially and spiritually American.” The sincerity of the petition is foiled by the underlying powerlessness of his position.

As the performance closes, Fujii enters wrapped in an amazing kimono made of hundreds of three-inch glass squares wired together at the corners. Each square features the picture of an ancestor.

While slowly progressing across the floor, the kimono tinkles, eerily reminiscent of wind chimes in a gentle breeze. Fujii, bearing the weight of the past, enters the now. This dramatic entry is made even more emotional when her daughter, following a few moments behind, enters the stage wearing a second kimono. This second kimono’s glass squares feature pictures of Fujii’s family as well as her husband’s family.

The room was electric with damp eyes as everyone discovered something about themselves and where they came from.

The work of Reiko Fujii is full of sincere, childlike wonder. The objects are beautifully crafted and lovingly thought out. But underneath, Fujii has chosen to share with us her most personal inner struggles, and in that sharing she helps us to acknowledge that we have our own as well. Fujii’s performance and the accompanying artwork are vehicles to help transport viewers to there own emergence.

The work is baptismal. We leave reborn and newly challenged.

In a world full of hard-edged, politicized cynicism, Fujii’s work delivers the contemplative serenity of a Japanese garden, mixed with the instant fright of a dream. The dreams of the past become the present reality as the present reality becomes the dream.

George Havelka